The club’s property can be tied to events dating back at least to 1732. The beautiful island we call home has, since the arrival of the Europeans, been a family estate, hospital, quarantine station, military prison, prisoner of war camp, recruit training station for the British Foreign Legion, ammunition depot and a yacht club. Wayward soldiers and sailors were jailed here as early as 1803. Beginning in 1808 French prisoners began arriving during the Napoleonic Wars. American prisoners captured during the war of 1812 also paid a reluctant visit to what by then had been named Melville Island after Henry Dundas, the Viscount Melville, a person of “provincial dialect and ungraceful manner”.

In the early years, the island changed hands many times between various civilian owners, the British Army and the Royal Navy. The Canadian Military took control of the four acre island in 1905. The stone prison on the site was used during the first World War to house German prisoners of war.

The Military moved out in 1945 and soon after, the founders of Armdale Yacht Club negotiated a long term lease for the land with the Department of National Defense Five buildings of that historic period remain. One of them is our club house. Built in 1808 it stands on the highest point of land on the island and gives a panoramic view of the Northwest Arm, the mooring field, marinas and yard activities. Pay a visit. Savor the legacy and the legend of Armdale Yacht Club.

A Detailed History Of Armdale Yacht Club By: J. P. LeBlanc

Incorporating the Armdale Yacht Club was not an event that suddenly rose from the sea floor of the Northwest Arm. It was years in the making. As the second oldest yacht club in Nova Scotia, Canada, AYC in its location has the longest association with sailing ships … bar none … certainly in Canada. At the mouth of the Northwest Arm is the oldest yacht club in North America. The Royal Nova Scotia Yacht Squadron has existed since 1837. AYC has history and legend… far more than can be written here.

In the 1920’s young men like Jack Buckley, Jim Egan, and Walter Piers led the way to the incorporation of the Armdale Yacht Club. First from a location close to Jubillee Road, then from ‘Mosey’ Stoneman’s Armdale Boat House and the Edmonds ground, AYC set itself up on Melville Island.

A 1930’s challenge with those who raced on Chocolate Lake brought others to the Arm. The ‘Siskin’ was an early power boat. During the prohibition era she knew about “rum running”. Louis ‘Tookie’ Murphy (AYC’s 2nd Commodore) later became Siskin’s proud owner. Jim Egan, AYC’s first Commodore, was the owner of the other power boat ‘Comber’.

When Mosey’s boathouse was torn down, a property on Edmond’s Grounds became the Club House. As membership grew, AYC moved to a second and larger house. The new location offered better moorings, a panorama of the Arm and a “great view of the races”. Then, twenty avid yachtsmen took steps to incorporate. This came from the efforts of Arthur J. Meagher and, passing by the Nova Scotia Legislature of the Armdale Yacht Club Act of 1937. The fee was set at twenty five (25) cents.

Following the end of WWII, interest in Melville Island began to grow. After much controversy, the site was awarded to the Naval Sailors Association. WC MacDonald (Member of Parliament) had this to say at a Halifax Kiwanis Club Meeting: “This is the only site in Halifax suitable for that group.” Walter Piers disagreed: “The place for the sailors’ group is Greenbank Cove.” The discussion with the Halifax MP and a visit to Greenbank Cove (now part of the Container Terminal at Point Pleasant Park in Halifax) prompted the MP to suggest that he might be able to convince Ottawa to change their decision. He was convinced that Greenbank Cove was a more convenient location for the Naval Sailors. In the days that followed, AYC was told that they had the lease on a year to year basis. Some say the late Senator Gordon B. Isnor had a hand in the decision.

On December 20th, 1947, the site was leased for recreational purposes to the Armdale Yacht Club on a year to year basis. The lease was renewed in 1952. Arthur J. Meagher negotiated the 99 years’ lease of June 20, 1956 with the Department of National Defense. The rent was set at $1.00 per year. Photos in the boardroom show the Clubhouse as it existed with the other buildings then in place. The Club has changed as the membership grew. The grounds were asphalted in 1971.

History is ageless. Halifax is gifted by its past. No other area in Canada has such a rich legacy and heritage. Sailing ships go back into the earliest annals of Nova Scotia’s history. They make their way across the Atlantic Ocean, to find anchorage in one of the deepest and finest harbors of the world. We find much of those historic roots and its rich heritage on the four acre island site at the head of Halifax’s Northwest Arm. It is a heritage that begins with the Micmacs. They used it before the founding of Halifax in 1749.

The Arm has changed its name many times in its history. The Micmacs called it Waegwoltic, meaning “deep river”, or “end of the bay”, or “salt water all the way up”. In 1732, it appeared as “Hawks River” on Captain Thomas Durell’s map. The British named it “Sandwich River”. Later Sailors, it’s said, renamed it the Northwest Arm because of its compass heading. The term ‘river’ stems from the misconception by early settlers the area was the mouth of a river.

Melville Island combines history with old buildings. The small islet is nestled at the center of the City. In 1752, the area now known as Melville Island was part of a land grant of 160 acres to two colonists, John Aubony (Aubenny) and Robert Cowie. The transaction was approved by Governor Cornwallis. Later that year an unsuccessful try was made to sell the property at a public auction. The ad in part read: “… included a 70 ft X 20 ft commodious store house, likewise a completely finished blockhouse with a stone chimney and two fireplaces. … persons that are inclined to make shingles, clapboards, laths, hoops etc. that place being very proper for that purpose may agree with said Aubony and Cowie very reasonably, from this time until… “.

Cowie (trader) died in 1775. He was buried at St. Paul’s Church in Halifax. Seven years later his estate was sold at public auction upon the orders of the Colonial Government to settle creditors. Two houses in Halifax, the 500 acres of land, including the Island (named Sandwich Island by Governor Cornwallis) were sold. Aubony (trader) had died in July 1754.

Cowie was among the first settlers to the province. His estate papers show that he had been a merchant and rum was one of his commodities. Cowie’s son, in a 1785 memorial, sought help for himself, his brothers and sisters. He told the government, that born of reputable parents, they had been cheated of their lawful property after their father’s death. Cowie’s estate papers (1781) refer to the sale of Cowie and Aubony’s Island and land on the Northwest Arm.

In January 1782, for thirty-eight pounds ten shillings of provincial currency, John Butler Kelly, the highest bidder, bought the land and the island on the west side of the head Northwest Arm. James Kavanaugh paid Kelly 65 pounds in May 1784 for the land that again included the Island. Kavanaugh built a house, huts to store fish and boats.

In 1794, two houses, on Melville Island, were rented two miles out of town for the sick and wounded French POW’s expected from St. Domingo. In June 1795, there were 27 patients in the prison hospital. In April 1796, sixteen soldiers were on duty.

In 1804, Kavanaugh and his wife sold their property in a presumably shrewd deal. The Commissioners for his Majesty’s Transport Service paid the Kavanaugh’s 1000 pounds. The deed refers to the Island commonly called Cowie’s or Kavanaugh’s Island. The Admiralty renamed it Melville Island. Henry Dundas, the Viscount Melville, a person of “provincial dialect and ungraceful manner” was impeached two years later. He was eventually acquitted.

The Island’s most colorful history, however, began with the military. Its upkeep over the years varied with their needs. In wartime it teemed with activity; in peacetime the buildings were often permitted to fall into disrepair and services reduced. In 1807, for example, extra fuel was given to the Military Personnel. None was made available to the prisoners. Those who brought fuel were pelted by the POW’s. Prisoners also broke windows in the officers quarters.

In August 1803 Melville was first used as internment for prisoners. Beginning in 1808, prisoners from the Napoleonic War and the war of 1812 were kept on the site. Ned Meyers and two other prisoners escaped by removing bars from their cell window. The three were later caught near Annapolis and returned to the “black hole” for ten days on bread and water.

French prisoners were given considerable freedom. Many of them spent their time making boxes, dominoes, knitted goods, bone trinkets and other hand made goods sold to local residents. Model ships of war were made of bone. The riggings were made out of hair. Artifacts of that era are still found in Halifax.

Entries in an 1814 diary by PJ Palmer reflect a historic and legendary past under the most primitive of conditions. The ships that conveyed the fortunate and unfortunates of the day were no less comfortable.

18 April – all hands looking for land. This afternoon made the long looked for land which were all glad to see. Although as yet uncertain of our Doom. It proves to be the west end of Sambro Light.

30 April – Light wind and thick weather I fear we shall not get in to-day. 4pm wind breezing up. Stood in for Sambro Light. Wind increasing and being fair we soon run up and came to anchor opposite the Town.

…marched three miles when we saw the gloomy walls of our new habitation.

7 May – Pleasant weather since I came to this damn’d hole – all hands employed washing out. – Good news in circulation. Some say peace and others say it is an armistice //hoax// – an exchange is to soon to take place as the report says, but reports are generally fabulous. This is the way most prisoners pass their time in collecting making and spreading all the news possible.

19 August – Farewell Melville. Never did I think I should leave this acursed prison with heavy heart.

Punishment was severe for the soldiers – more so than for the prisoners. Soldiers returning drunk from escort duty to Halifax were lashed; those purchasing goods from the inmates were court-martialed. Lieutenant A. Keough, an officer in the 64th Regt., was cashiered for drunkenness. Branding, an old form of punishment for deserters with the letter ‘D’ still existed in the mid 1800’s. Freedom for the prisoners came with the downfall of Napoleon and the end of the war of 1812.

A notice to inhabitants appearing in the newspaper Acadian Recorder of October 2, 1813, in part read: “…having POW’s sent them from the Department at Melville Island”. The residents of the area were asked to return the prisoners-of-war for a meeting. A separate ad invited men to apply for two positions at Melville. In part the ad read: “to do the duty of turnkeys for the service of the POW Department.”

By 1829, ten buildings and a garden covered the surface of Melville. The prison, a long wooden house two stories high, was in a state of neglect and decay. A wooden bridge connected the Island to the mainland. On a small hill to the southwards was the burying ground belonging to the Island.

In 1855, the Island was placed at the disposal of the British Army by the Royal Navy. It was to be used for the reception of the expected recruits for the British Foreign Legion. Landing at Queen’s Wharf, in Dartmouth, recruits marched to the Island. There they were housed in a building formerly occupied by French prisoners.

A drawing for the Illustrated London News of May 19, 1855 reveals that several buildings were already standing on the site. Barracks for the Foreign Legion were on the west side. A house stood on its highest point with several smaller buildings, including a stable, a shed, a cook house and a wash house. The guardhouse was immediately across the bridge. There was also a well for water.

In an emergency, the facility could have held from 1300 to 1500 with hammocks suspended over one another. The London Illustrated News also reported, “… The situation of Melville Island is remarkably picturesque and in the summer it is a great resort of ladies of Halifax for picnics and lobster spearing…”

In 1856 the Island was no longer a Royal Navy Prison. With the transfer to the British War Department, it became a regular military prison for backsliding soldiers. In January the number of prisoners stood at 70 with only two of the buildings being occupied. Lists of personnel committed to the Detention Barracks contain names of soldiers of various units in the area. The lists cover the years 1867 to 1871. A few seamen were also in detention. “Theft, insubordination, drunkenness, desertion, selling a pair of boots, AWOL, leaving his guard,” were the most common reasons for the commitments.

During periods of military lull Melville was available for other purposes. Seeking refuge with British Troops deserting Black Slaves, numbering some 800, used the site as a temporary station during 1815 and 1816. At least 1/8th of them died of smallpox. By June, all the survivors had left for other areas of Nova Scotia.

During the summer of 1847, immigrants with typhus fever were moved to the Island. These steps were taken to protect the Garrison and inhabitants of Halifax. Thirty-seven, mostly aged, died. The hospital remained open from June until October.

The British North America Act of 1867 shifted responsibilities for the Island from England to the Dominion Government in Ottawa. In 1884 a new stone prison with 34 cells was built. In 1905, the Canadian Army took over the site. In 1909, the name was changed from “Military Prison” to “Detention Barracks”. The last army detainee of that era was released in March of that year. The stone prison was used during the First World War for German prisoners-of-war.

Contrary to some reports, Leon Trotsky, the historical Russian rabid revolutionary, was not a prisoner here. Following his arrest aboard ship on April 3, he was transferred to the POW Camp in Amherst. There he remained until released.

Military activities ceased in 1945. In 1941, when the Royal Canadian Regiment – the RCR’s – transferred to McNab’s Island, the site became an ammunition Depot.

Residents of the area remember the large containers stacked on Melville. They believed that they contained mustard gas. They also talked about Germans coming ashore to buy goods from a general store in Herring Cove. Their greatest fear was that the U-boats lurking offshore could lob shells on the Depot with catastrophic results.

A house put up for the warden in 1808, standing on the Island’s highest point, serves as the Clubhouse for the Armdale Yacht Club. Five buildings of that historic past remain. The property in 1947 consisted of eleven buildings in various stages of disrepair. Wooden buildings highlighted in Thomas Raddall’s writings were destroyed by fire in 1935.

If only the walls of the various buildings, the ground upon which walked its residents, the small bridge, or the ships that led there could talk, what further revealing, intriguing and fascinating tales could be told. The saddest would likely be that of the young scullery maid. She was accused of having stolen a silver spoon during a snow storm. When the snow cleared, the cutlery was found where it had been left. Unfortunately, it was too late to save the young woman. She had already been hanged.

AYC continues to foster self reliance among its members in the maintenance of their boats. The Club’s character, however, has altered over the years – from open Snipes, Sabots, Bluenoses, Roues, two power boats to bigger power boats and fiberglass auxiliary sail boats.

In a breathtaking setting replete with history, AYC finds no equal in Canada. The Armdale Yacht Club offers a complete range of facilities and services to meet the needs of todays yachtsmen.

This area of our web site is intended for members who would like to share some history about The Days Gone By

The current entry has been provided by: Barrie MacLeod

Mr. Gilkie (1) lived in Melville Cove and was Ron’s grandfather. The monkey belonged to Ernie Cameron. If you think there are some characters at the club now, you have no idea of the stuff that went on in 1950. Speaking of characters, “Gibby”, Mr. Roy Gibb skippered Dr. Arthur Marshall’s Roué 20 and took nurses and six year olds like me sailing. Mrs Gibb convened the teas after the races with real, sterling silver trays, coffee pots and cute little sandwiches.

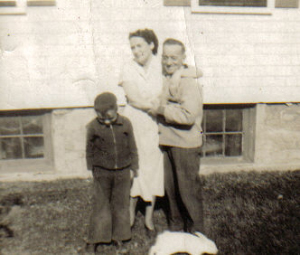

“Gibby” (2) is shown here in 1950 with me (Barrie MacLeod), my mom Irene MacLeod and a rabbit that one of the members brought to the club for me. Other members gave me Lionel Trains and drove me to Sunday school as, of course, the club was open on Sunday and my parents were the stewards and we lived upstairs. Then we moved across the street and joined as members. I spent from 4 years old to 16 years old at the club and the members were, without exception, good, kind and generous to me. Stephen Penny’s father, Frank, taught myself, Roy Levin and dozens of others to swim and sail. The water was clean enough in 1950 that we swam every day off the wharves at AYC and it was a tradition to toss the winner of races into the drink. In the windows of the basement are beautiful models of warships. The bar was down there in the small area where the lower bar is now. The present bar and lower area where darts are played was another build on in the 1950s. Members brought in their own bottles of booze and put them on what was called corkage. You drank your own stuff. If you didn’t drink someone stuck your name on a bottle and there was extra for all.

This house on Dead man’s Island (3) was torn down around 1992. There was another house on the island closer to the mainland. When Mr. Boness would dig out a bit of the hill behind his house, it was not uncommon to come across a skeleton and, as I remember it, the N.S. Museum would come and take it. In the winter an arm might stick out of the bank until spring when the rest could be dug out. his photo was given to me in the 1950s by member Steve Sebago’s ‘ daughter Valerie.

Barrie MacLeod and Roy Levin had lunch at AYC. on Sunday. January 19, 2004 as usual. This photo (4) was taken in 1950 when we were out sailing on JETO (Jessie & Tom), a Tancook schooner owned by Imperial Oil Captain Tom Mountain. In the photo we are on Smitty’s harbor craft looking at two of the Bill Lynch Show ponies being ferried to McNab’s Island. When we were a little older we would sail ourselves to McNab’s and try to jump on the ponies for a ride. Lynches owned land on the island and the ponies ran free on the island in the 1950s.

The boy standing on the steps is me, (5) Barrie MacLeod, in 1950. The steps went into what is now the dining room but was then the sun porch. There was no deck in front of it then. There were Adirondack chairs, in bright colors, on the lawn by the flag pole and on the roof of what is now the dining room. The present main entrance is a “new” build on.

Barrie MacLeod – AYC – SKYEBOAT.